For a small place, my home state of New Hampshire puts up some pretty impressive numbers.

For example, we have 424 members in our state legislature, the fourth-largest English-speaking legislative body in the world, smaller only than the U.S. Congress and the Parliaments of Great Britain and India. Given that our population is only 1.2 million (for the record, that’s 1/1000 of India’s), that means that we more or less have a representative on every block. Sometimes, two.

Similarly, this small state has over 8,400 nonprofits, of which about 1,600 are viable entities with budgets of over $100,000 and at least one paid staff member. And of these 1,600 viable nonprofits, there are fewer than a dozen that have staff members whose title includes the term “planned giving.”

In New Hampshire, and elsewhere, the less-than-1% of nonprofits that can afford it are investing heavily in planned giving. The other 99% can barely afford to go through the motions.

Why does it matter?

Because planned giving is where the money is.

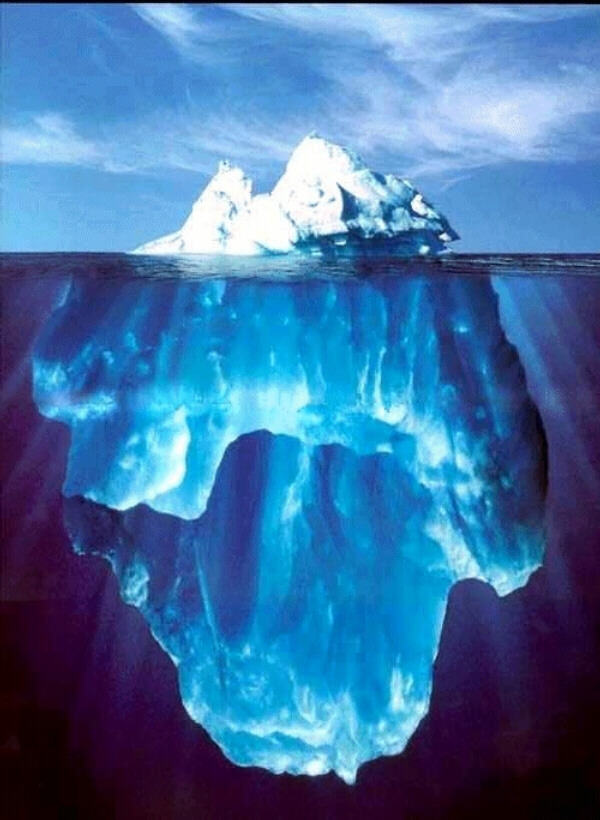

Think of the financial resources of a high net-worth individual as an iceberg. The portion above the water line – the readily visible part – represents that person’s income. That’s the part that’s scrutinized: How much does this person earn? How does this person spend his or her money? And, from a typical fundraising perspective, how much of that income can we get for our organization?

But the real wealth lies below the surface. That represents the assets – the businesses, the stock and bond portfolios, the real estate – that make the income possible. The below-the-water-line assets also include non-income-producing items of great value, like art collections and antique cars.

The reason planned giving is so important? Because it’s about the assets, not the income. And that’s where the wealth is. Here’s my definition of planned giving: The charitable distribution of assets at the time of, or in anticipation of death. It’s taking a chunk of those below-the-water-line assets and conveying them to charitable purposes, sometimes though fancy life-income instruments, and more often through simple bequests.

So what can the 99% of nonprofits without a planned giving staff do to acquire these gifts? Plenty – but the how-to will have to await my next blog post. In the meantime, keep your eye out for submerged icebergs, and if you have thoughts on the subject, send them along!

Copyright 2012 Alan Cantor. All rights reserved.

3 Comments. Leave new

Entering the conversation about “a distribution of assets at the time of, or in anticipation of death” means first that we have been fortunate over time to have developed an open and honest relationship/friendship with these individuals.Thanks Al for priming the pump…..I am looking forward to your next blog post!

Brian

Thanks, Brian!

Two things Americans are notoriously reluctant to do are to contemplate death and to ask for money. That makes planned giving conversations a wee bit tricky. But you’re right — if you already have an open and honest relationship, it’s possible to turn to this subject rather naturally. I’ve also seen a trend where those folks who have decided to move to retirement and continuing care communities have essentially already accepted their mortality, and they jump right into conversations about planned giving with remarkable ease.

I’m also looking forward to reading more along these lines. I’ve explored some of the investment options that make this possible earlier, but just enough to know that the exist and are relatively untapped.