Fewer and fewer Americans are making charitable contributions, and we need to ask ourselves why.

Certainly, economics plays a major role. “Gilded Giving 2018,”a report from the Institute for Policy Studies, shows that about 18% of families that historically donated to charity fell out of the habit with the Great Recession, and they haven’t come back into the fold. According to detailed studies enumerated in that same report, middle-class and upper-middle class donors have melted away, a downward trend that closely tracks economic measures such as the reduction in home ownership and falling labor force participation rates.

Meanwhile, overall charitable giving fell in 2018, with a particular drop-off in contributions from individuals. This is the first time in decades that charitable giving has fallen in a year when the economy, by conventional measures such as GDP and unemployment, was doing well.

Last year’s drop in charitable giving was sadly predictable. I’m neither an economist nor a futurist, but as I wrote in December 2017, donations were likely to go down because the government had dramatically curtailed incentives for charitable giving. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which was rushed through Congress without any meaningful public review, effectively removed any tax incentive for millions of taxpayers to give to charity. Before this bill, 30% of taxpayers claimed itemized deductions, and, therefore, could deduct their charitable gifts. But the Tax Act doubled the standard deduction, which meant that the percentage of taxpayers itemizing their deductions dropped to only 10% in 2018. The charitable deduction is now in effect only for what are essentially the richest 10% of taxpayers. The rest of us get no encouragement through tax incentives to support charity.

Republican Congressional leaders who rammed through the tax bill knew that it would undermine charitable giving by disincentivizing middle- and upper-middle-class donors. They just didn’t give a damn. And charitable giving may drop further in 2019, now that millions of people, having filed one year’s taxes under the new rules, are wise to how charitable giving no longer gives them any financial advantage.

But the reduction in charitable giving and the shrinkage of the donor base goes beyond economics. I think there’s more here that’s suppressing charitable giving – which brings me to the psychological impact of living in a stressful, pessimistic, and unidealistic time.

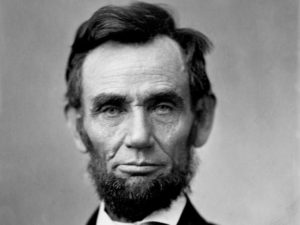

In the past, our political leaders spoke inspirationally about charitable giving – and of committing ourselves to making the country better. Think of the memorable inaugural addresses in our history. John F. Kennedy famously urged us to ask not what our country could do for us, but what we could do for the country. George H.W. Bush spoke of the thousand points of lights – the volunteer efforts that make America great. Franklin Roosevelt reminded us that we had nothing to fear but fear itself. Going further back, Abraham Lincoln appealed to our better angels – even as the Civil War still raged. These leaders inspired. Imperfect though our union has been, we Americans felt a compulsion to improve both the country and our own condition. We invested in our communities. In fact, giving back in large part defined America. Alexis de Tocqueville, in his 1835 Democracy in America, marveled at Americans’ unique inclination to form volunteer associations and contribute their time and money.

By contrast, the current president’s inaugural address will be remembered for his reference to “American carnage.” He has consistently labeled Latino immigrants as rapists and criminals and Muslims as terrorists. He refers to African American neighborhoods as unlivable and dangerous. He is a singularly uncharitable individual – a man whose personal foundation was shut down by the New York AG’s office for corruption and self-dealing. A chilling lack of empathy pervades the president’s public and private statements and interactions. He feeds a strand of American society that says, “We have ours; let’s not worry about anyone else getting theirs.” His is the politics of “us vs. them,” which conflicts with the charitable sector’s historic commitment to all of us working together and caring about everyone.

Meanwhile, people are understandably on edge about the impact of Mr. Trump’s economic policies. The U.S. hadn’t seriously considered a trade war in decades, let alone impulsively rushed into one. (As I write, China’s retaliatory measures are hammering the stock market – where, of course, those of us who are able to save for retirement have invested our assets. More stress.) Where will our farmers sell their soybeans? What are the implications of the sky-rocketing deficits? The threats to the Affordable Care Act? The future of Social Security?

It’s worrying stuff. People are concerned that they won’t be able to afford healthcare for their families or college for their children. They ask themselves if they can avoid medically-related financial catastrophe (that is, bankruptcy) before they qualify for Medicare – if, indeed, Medicare will still exist at all. They wonder if they will be able to retire – ever. Even the weather forecasts bring stress, as people worry more than ever about severe weather, fires, flooding, and drought.

Worried people are not terribly charitable. They hoard their resources for, well, whatever unexpected madness comes down the road. They take care of their own.

There are two areas of hope for the nonprofit community. The first is that charitable giving feels good. Giving makes the donor feel happy, providing what economist James Andreoni has called “the warm glow” – and, certainly, people in a challenging time need an injection of happiness. Charitable giving connects donors to a larger community. It provides comfort to the giver, as well as the receiver.

Second, many people are inspired to fight what they see as bad policies through charitable contributions. This means that some causes, such as those that support immigrants, civil liberties, the environment, and women’s health, are clearly attracting new donations in response to the administration’s policies. Many other organizations can draw on that impulse, without making an explicitly political argument. They can assert that “now, more than ever” donors are needed to support soup kitchens, intervention programs for kids, home health services, housing for veterans, or scholarships.

So what’s the future of charitable giving? Will the nonprofit sector reengage with lost donors and regain its stride – essentially overcoming the impediments of economic anxiety, reduced tax benefits, and societal stress? Or are we witnessing the acceleration of the trend whereby middle-class families are abandoning charitable giving and philanthropy is becoming a rich person’s game? And will the troubling trends turn around with a new administration in January 2021 – assuming there is a change in leadership?

I won’t hazard any guesses, though I think we’re in uncharted territory as a nation and as a charitable sector. The skies are dark, and the winds are whipping. Donors are furling their sails and battening down the hatches. At least for the next year or two, I fear we’re in for a rough voyage.

Copyright Alan Cantor 2019. All rights reserved.

5 Comments. Leave new

I always value your perspective, Al, thanks! Here in the non-profit professional theatre world, it is our fervent hope (and belief) that in times like these donors (and ticket buyers) see a particular value in supporting the performing arts. We continue to strive to bring a sense of community and moments of joy and hope to our very troubled world.

And, yes, I think that makes sense, Mary Beth. Hope you’re well!

One more thought–again driven by current times–I find myself thinking “should I give a small amount to the ‘cure a given disease’ foundation [or whatever charity] as in the past, or should I direct that money to a Democratic candidate now that I have fallen out of the category of deduction-itemizing taxpayers?” Supporting Democratic candidates, quite frankly, seems more important today.

Spot on. It’s very hard to talk about fear and the reality of our times. Acknowledgement is the first step toward change–or at least a shift in strategy. Right? I would like to add that I think most presidential election years are challenging for fundraisers, as some donors shift resources to support a candidate or political party. I do anticipate a particularly challenging 2020.

Thanks, Doreen. Yes, there is competition with political giving, for sure, particularly in a time like we’re going through. As Chris Smith notes in these comments, he’d argue (and many do) that it’s more effective simply to make the political contribution. That’s part of the challenge here. Thanks for weighing in and for your thoughtful comments.