The boarding school I attended recently announced a $25 million gift from one of its trustees.

I don’t begrudge my alma mater its big gift. I’ll also note that the donor is a gracious and generous man – I’ve met him once or twice. And the funds are directed for scholarships, which I applaud. But it did get me thinking about what that money could have done at a less prestigious institution serving less affluent students, and why the chance of a gift of that magnitude going to, say, a community college, is next to nothing.

As a consultant, I research theories that answer these questions – and then, when I can’t find an existing theory, I make one up. That’s what I’ve done here, and I’d now like to share what I’ve drafted for your review and reaction.

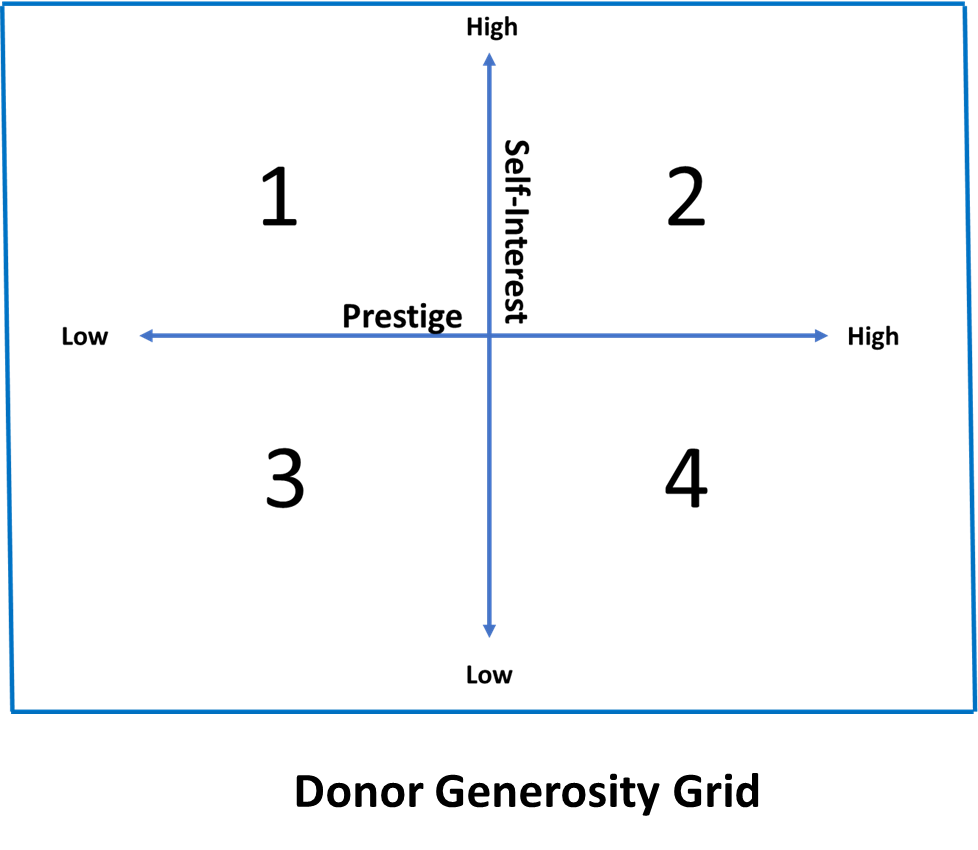

At that aforementioned fancy prep school, I was a pretty good math student – that is, until I ran into a trigonometrical wall in eleventh grade and decided, well, maybe I’m better with words than numbers. But I do know my x-axis from my y-axis, and so here’s my take on what I’m calling the Donor Generosity Grid. (Note, once more, that there is zero scientific validity behind this grid.)

The horizontal axis is a measure of organizational prestige, from low prestige on the left to high prestige on the right. The vertical axis represents donors’ self-interest, from low self-interest at the bottom to high self-interest at the top: that is, how much the donors themselves benefit from the charitable organization. And the simple theory is this: The higher the combined measure of organizational prestige and donors’ self-interest, the larger the top charitable gifts.

The prestige scale seems obvious. But what do I mean by self-interest?

Let’s start with the most successful fundraising organizations, which are almost all clustered in Quadrant 2: the high-prestige/high-self-interest institutions. For example, take the Metropolitan Opera. It’s extremely high prestige — I mean, it’s the Metropolitan Opera, after all! — but it also provides donors with direct benefits. The donors get to see great opera, which improves the quality of their lives. In fact, the bigger donors generally get the most comfortable and coveted seats at performances. Similarly, patrons of prestigious museums experience great art, and they also get to attend special donor events with the artists and curators.

Not all the Quadrant 2 organizations are in the arts. Self-interest takes many forms. For example, donors to land conservation groups help conserve critical habitat. I support land conservation with all my heart, but we have to recognize that frequently, in the process, donors also preserve the view from their living room windows, or access to hiking trails for their families. As for donors to elite prep schools and universities? Again, the prestige is obvious. But let’s also recognize the self-interest. When the institution thrives, the donor’s own diploma is worth more. Moreover, given the sometimes acknowledged and often unspoken preferences given to children and grandchildren of alumni and donors, charitable gifts can ease the path for family members to attend the school.

(Please, please, please: Don’t take my comments about donors’ self-interest to mean that I think there’s anything nefarious or shady about the donors’ intent, or that these organizations are less worthy than others. Some of my favorite charities — and clients! — live in Quadrant 2. I’m simply suggesting this lens for understanding what motivates major charitable giving.)

It’s Harder in the Nonprofit Hinterlands.

Nonprofits in the other quadrants struggle to match what Quadrant 2 has to offer. Quadrant 1 (low prestige/high self-interest) is populated by institutions like nonprofit childcare centers, where the parents — generally at a financially strapped and stressed time of their lives — are desperate to fund the centers so they can retain their childcare. The donors have significant self-interest in the survival of the organization, but the childcare center has neither prestige nor the resources or connections to attract significant gifts.

Quadrant 3 (low-prestige/low self-interest) includes organizations like food pantries, homeless shelters, drug rehab programs, community colleges, and housing groups. Virtually everyone agrees that these are vital organizations for the community, but wealthy donors don’t usually receive benefit themselves. Moreover, there is a general sense that these are institutions working on issues that many donors simply would prefer not to think about.

Quadrant 4 (high prestige/low self-interest) includes the relatively small group of social service organizations that have positioned themselves as THE charitable cause in the region. They may be working on gritty issues, but they’ve taken on a smidgeon of glamor in the community — a bit of prestige. For example, in a small city near me, the major organization serving the homeless has an annual gala that has evolved into the can’t-miss social event of the year. That evening — and throughout the year — the organization raises truly significant dollars. But that’s the exception to the rule: It’s tough for human services organizations to break out of Quadrant 3 and slide into Quadrant 4.

And What Does Any of This Mean?

Let’s take a moment and decide to agree (for argument’s sake) that this four-quadrant structure has some validity. So what should we do about it?

If you’re a nonprofit leader, I suppose the first step should be to identify where your organization lives. If you’re in Quadrant 2, it might be good to recognize that you have natural advantages, and that your fundraising success may be more a factor of what your organization is rather than what you are specifically doing to attract money. (It’s petty of me, I know, but over the years I’ve come to think that some Quadrant 2 fundraisers could benefit from a bit more humility.)

As for everyone else, first, you might take a moment to appreciate that if you’re not raising the kind of money that Harvard or the Museum of Fine Arts brings in, that’s entirely understandable. Board members, in particular, need to be careful about transferring Quadrant 2 expectations into the more challenging worlds of these other nonprofits. That said, you might work on your development messaging to add overtones of prestige and self-interest.

In terms of prestige, it’s hard to get people to treat a soup kitchen or a homeless shelter or a childcare center as an elite institution, but you might play up testimonials from mayors or celebrities talking about how important and well-run the institution is, so as to suggest, wherever appropriate, that you’re a first-in-class and deeply respected organization. As for self-interest, you might work to make connections between the organization’s mission and the benefit to the donors. That is, you might suggest that your organization’s progress on social issues around housing or education or food insecurity or addiction recovery is making the community better for business, better for families, better in general. Everyone benefits from the organization’s work, not only the indigent, the homeless, and the addicted.

A lot of nonprofits already do this kind of messaging, consciously or not. But perhaps a more intentional effort would be helpful, so long as it’s done respectfully and appropriately.

Changing the Donor Mindset.

But to me, the real question is how to get donors to think differently. I’m sure the gentleman who gave $25 million to my prep school also supports his local food pantry, and maybe even the community college in his city, but he probably gives them each $1,000 or so, not a seven- or eight-figure gift. And I don’t think these smaller nonprofits should let him and other high-net-worth donors off the hook.

Those of us running vital but less advantaged organizations in Quadrants 1, 3, and 4 need to ask high-net-worth individuals and foundations to give donations at higher levels. Your local community college probably serves many times the number of students as the prep school I’ve mentioned; the vast majority of the community college students are from families with low incomes; virtually all of the community college students are the first generation in their families ever to attend college; and successful community college graduates will fill critical roles in our communities — nurses, teachers, accountants, dental hygienists, IT professionals, etc. Perhaps what’s most compelling: a million dollars at a community college would go incomparably farther, providing vastly more scholarship support, than the same amount would at an elite school, because community college tuition is so much lower. There’s real, measurable, transformational impact.

The $100 Million Example.

Of course, some donors get it. I love the story of Hank Rowan, a philanthropist who was approached for a $10,000 gift by Glassboro State College (now called, for reasons that will become obvious, Rowan State University), a tiny public institution in New Jersey. Rowan responded by asking, “How about if we make it $100 million? What would you do with that?”

And what they did was create a robust school of engineering (Rowan was himself an engineer) serving hundreds of first-generation college students every year. In a memorable podcast, “My Little Hundred Million,” Malcolm Gladwell describes how Rowan decided not to give that money to MIT, his own alma mater, widely considered among the best engineering universities in the country. Rowan didn’t want to gold plate the already-superb education that the top students received at MIT or Stanford or Cal Tech. No: He wanted to give opportunity to capable but less exceptional and less privileged students — and to help society by filling the workforce with skilled engineers. He knew that $100 million to MIT wouldn’t change the world, but that $100 million to a less prestigious university would make a very real difference for thousands of students, and to the community. As Gladwell puts it, Rowan saw society as a chain, one that is only as strong as its weakest link. He wanted to invest in the weakest links, not the strongest links.

Rowan’s gift to Glassboro State was the first nine-figure gift ever in the U.S. to an institution of higher education. Since that moment in 1992, there have been over a 100 gifts at that level to universities — but virtually all of them were to elite institutions squarely in what I’m calling Quadrant 2, a fact that Gladwell bemoans colorfully in the podcast. I would peg Glassboro State pre-Rowan as being in Quadrant 3 — the land of low self-interest and low prestige. Hank Rowan set a remarkable precedent, but in the three decades since, other large donors for the most part have not chosen to follow his path.

Let’s acknowledge the inherent hierarchy of charitable institutions — but at the same time, let’s not accept that all the big money will always go to the Quadrant 2 organizations. Nonprofits: I urge you to suggest bigger gifts to donors and talk about the major advantage you have over the Quadrant 2 institutions: Impact! And donors: Think about what a difference it would make if your largest gifts went to the less prestigious organizations serving populations truly in need of opportunity. Jackie Robinson famously said that a life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives. Hank Rowan understood that. Let’s hope that, in the coming years, and at a time of ever-growing wealth inequality, others do the same.

Copyright Alan Cantor 2022. All rights reserved.

21 Comments. Leave new

Great piece as usual, Alan!

Here’s to us valuing impact more in society to help inspire such a shift-

Thanks, Dennis!

Good piece, Al. I think institutional prestige and self-interest are largely two sides of the same coin for high net worth donors; the former is a key ingredient in what feeds the ego and builds social capital in certain social circles both which are a part of the latter. Maybe there are opportunities for fundraisers outside of your Q2 to tap the desire of some donors to be perceived as being leaders in creating prestigious institutions rather than a well heeled sheep. I doubt that’s what motivated Rowan’s gift but Gladwell wouldn’t do a podcast on Rowan if he gave $100M to MIT or Harvard.

Thanks to Mackenzie Scott for setting a good example to change this matrix, and as someone who spent a lot of time trying to figure out the matrix BEFORE reading the text, I might suggest that you re number your squares to correspond with the size of the expected gifts.

Thanks, Susan!

You’re right — MacKenzie Scott listens to a different — and an impact-focused — drummer, and she does a really nice job of funding those Quadrant 1, 3, and 4 organizations.

As for the numbering — ha! you know me! — I was playing around with just that kind of scheme. But I finally decided to go with what is standard (largely drawn from Stephen Covey’s work), particularly as it would be hard to rank order beyond what are (in my scheme) Quadrants 2 (richest) and 3 (poorest).

Really good food for thought Al. Even for those of us not in the seven-figure-donation category! (Local) Impact over (perceived) self-interest is a really rational guide to giving

Thanks, Peter! It’s kind of you to read this and to weigh in. I trust you and Robin are well?

Al, as always, you made my day and made me think about NH Gives. Sometimes volume counts.

My organization, which sits in Q3, earned a few prestige points by winning the prize for the largest number of donations (most of them small) in Hillsborough County. They added up to a respectable, if not transformational, total.

Thanks, Rick. Yep, that’s a way to gin up some prestige for what’s definitely a Q3 enterprise. Thanks for writing — and best to you and Susana!

Imagine if donors stepped back and looked at the bigger picture. I suspect this line would resonate moreso-successful community college graduates will fill critical roles in our communities — nurses, teachers, accountants, dental hygienists, IT professionals, etc.

Great article, thanks for shedding some light on this.

Thanks so much, Elaine! Great to hear from you!

Well said as usual Alan. The gap is widening and the fabric of our civil and democratic society is perilously frayed. We all have to do better about focusing our donors on philanthropic impact and leverage.

Thanks, Bob, for your thoughtful comment. I really appreciate it, and it’s good to know that we’re aligned in looking at this issue.

Hope you are well!

Good piece, Al. I think institutional prestige and self-interest are largely two sides of the same coin for high net worth donors; the former is a key ingredient in what feeds the ego and builds social capital in certain social circles both which are a part of the latter. Maybe there are opportunities for fundraisers outside of your Q2 to tap the desire of some donors to be perceived as being leaders in creating prestigious institutions rather than a well heeled sheep. I doubt that’s what motivated Rowan’s gift but Gladwell wouldn’t do a podcast on Rowan if he gave $100M to MIT or Harvard.

Thanks, Josh. Smart observations. Yeah, I think what would be great is if giving tons of money to hinterland nonprofits became the cool thing to do, the kind of gift that gets positive attention from other donors. We’ve seen lots of transformations of what is cool in society. It used to be that smoking at a bar was cool; now that person would be a pariah — and would be escorted out. Driving a Hummer used to be cool (and it still is, with some folks), but an all-electric car is way cooler. We need a similar transformation for philanthropists.

Al,

Your Quadrant is an excellent thought guide for both the Donor and the Organization seeking Donors. Being an engineer I also get your two dimensional guide in a three dimensional manner, where you gave examples. For instance High Prestige can be Local, Regional, National or Global. High Prestige can also be viewed in terms of how they are viewed in a Subject-Matter Group (e.g. Cancer, education, Elderly Care, etc.)

I particularly appreciated you magnifying the financial impact a donation can bring to an Organization. It’s not only the amount, it’s what impact that donation can do for the population that the non-profit was set up to serve.

Again, thank you.

Thanks, Richard, for your generous words. Yes, I think you’re right: the Quadrants can apply locally and regionally. Within a small city, the most prestigious performing arts center or orchestra can be anchored in Quadrant 2 — even though they’re not the Metropolitan Opera or Lincoln Center. And, certainly, prestige depends on the company the donor keeps. This is especially true, I think, in religious charities.

Impact will be a new consideration for my future donations. There are so many good causes seeking support and most of us have to choose where to donate. Thanks for opening my mind to impact!

(I imagine social justice causes and political candidates would need a different chart.)

Thanks, Susan, for your kind words. Like most simple theories, this quadrant doesn’t answer all the complexities of the real world — but it does get us thinking.

Thanks to Vu Le, this latecomer is onboard more than a year later, and sorry that, for all my years among nonprofits, it’s only now that I have begun to take in and enjoy your well-put wisdom. What triggered your excellent piece reminded me that the boarding school at which I was a fitful day student 70 some odd years ago had its own recent version of the scenario you describe — the major differences being that 1) the mega gift is being used to construct a new building, and 2) I only went so far as to contemplate writing to complain about what struck me as the egoistic trappings of the event. Even had I acted rather than groused, it would have resulted in nothing approaching the value of what you’ve hatched here. I particularly appreciate it because the bulk of my collective, modest efforts for years to provide value to people active in the nonprofit sector have centered on those organizations in your Quadrants 1 & 3 — many grassroots outfits, whose strained efforts to find support and support themselves lent credence to what I was sharing with them. So, thanks for your efforts here and with them there “who-bodies.”

Thanks, Harvey! I’m honored by your comments, both about this piece and the Who-bodies post of October 2023! Let’s stay in touch!